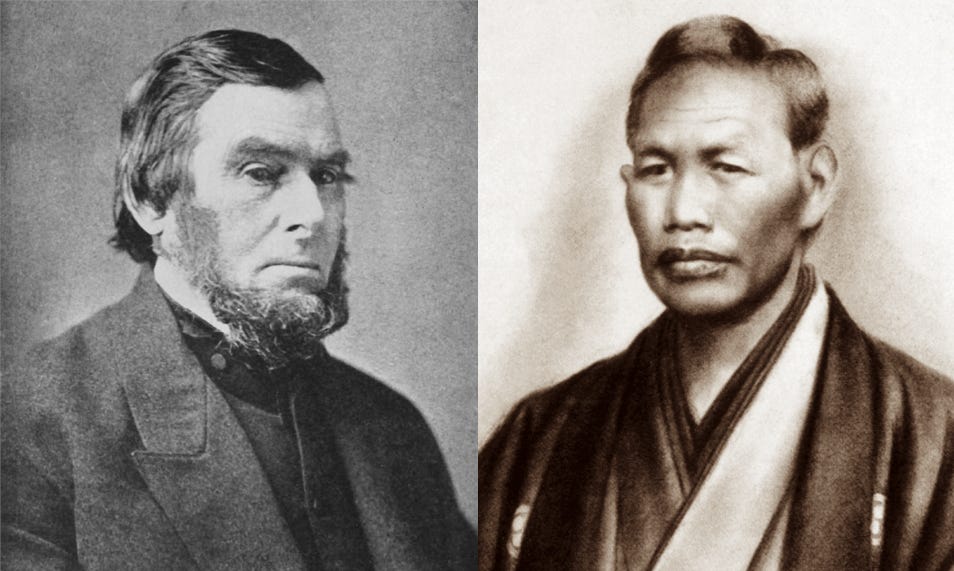

Samurai "John"

Fairhaven was home to the first Japanese person to live in the United States

The Manjiro Story is the stuff of fiction—poor, fatherless teenage fisherman stranded on a Pacific island becomes the first Japanese person to live in America and makes his way back to his homeland just in time to play a role in Commodore Perry’s effort to open Japan to western trade. Along the way there are adventures at sea, acceptance by strangers in a small New England town, a side trip to California during the Gold Rush, and months in prison upon first returning to Japan. Finally, following trips back to America with diplomatic missions and an important position as a professor of navigation and ship engineering at the university in Tokyo, the former village fisherman remains a national folk hero more than 180 years later. Here we find nearly all the classic elements of an intricately plotted historical novel—and then some. An unidentified editorial writer in the December 1956 issue of American Heritage said the account of Manjiro’s adventures is “so strange and charming that it reads like a fairy tale.”

Yet the story is true. And Fairhaven plays a key role in the story.

In January 1841, Manjiro Nakahama was fourteen years old when he and four other fishermen, blown off course in a storm, were washed ashore on the tiny island of Torishima, hundreds of miles southeast of Japan in the Pacific Ocean. The castaways’ boat was wrecked on the island’s rocks and their tools and equipment were lost. For six months the five survived by eating shellfish, seaweed and albatross.

Then, on a Sunday in June, the New Bedford whaleship John Howland, commanded by Captain William H. Whitfield of Fairhaven, arrived at the island. Crew members of the John Howland, ashore in search of turtles, found the half-starved men and brought then back to the ship. Captain Whitfield and his crew could not understand anything from the men except for the fact that they were hungry. The Japanese men were fed and soon regained their strength. Manjiro quickly befriended the ship’s crew and was soon acting as a lookout, spotting whales. The boy was nicknamed “John Mung,” which the crew found easier to pronounce. Upon the John Howland’s arrival at Hawaii, four of the men remained at the town of Honolulu. However, Manjiro, who was already speaking English quite well, accepted Captain Whitfield’s invitation to continue the voyage and return to Fairhaven.

Captain Whitfield’s ship returned to New Bedford in May 1843. Manjiro most likely spent his first night in America at Whitfield’s house on Cherry Street in Fairhaven. Whitfield was a widower at this time. During the time before the Captain’s remarriage, Manjiro was boarded with Whitfield’s friend Ebenezer Akin, who lived around the corner on Oxford Street. Akin’s next door neighbor, Miss Jane Allen, offered to tutor Manjiro in English. Soon the boy began attending the little stone schoolhouse on North Street.

Following Captain Whitfield’s wedding, he purchased a farm on Sconticut Neck and set about building a house there. Manjiro helped in the construction of the home and move in with the Whitfields when the house was done. There he worked on the farm and continued his studies at the district school on Sconticut Neck. Whitfield then enrolled Manjiro in the Spring Street school of Louis Bartlett, who taught mathematics, navigation and surveying. He studied with Bartlett for two and a half years and was an excellent student. Manjiro also learned the trade of barrel making as a cooper’s apprentice.

Manjiro was obviously an exceptionally bright young man. Never able to attend school in Japan, Manjiro could neither read nor write in Japanese. Yet he managed in the latter half of his teens to learn to read and write English well enough so that he could, after his return to Japan, translate Nathaniel Bowditch’s The New American Practical Navigator into his native language.

It was probably to Manjiro’s advantage that New Bedford and Fairhaven were rather cosmopolitan places at the time he arrived here. The local population was constantly in contact with foreigners associated with whaling and other maritime ventures. In Fairhaven, especially among those associated with the Unitarian Church, anti-slavery organizations were being formed. It’s true that two churches in Fairhaven would not allow Manjiro to sit in the same pew with the Whitfields, but at the Unitarian Church he was accepted as an equal. He fit in with his classmates at school, too—he was considered rather quiet, but friendly.

Ironically, the church that accepted Manjiro was built by the great-grandfather of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. As a boy visiting the Delano homestead, FDR was told by his grandfather, Warren Delano, how Manjiro often went to church with the Whitfields and the Delanos. That Fairhaven has such a close connection with both the Japanese man who introduced America to his countrymen and the American President who was caught in a war with Japan is a coincidence that no novelist would create for fear it seem too contrived.

After three years of living and studying in Fairhaven, Manjiro joined the crew of the whaleship Franklin as a cooper. The voyage was completed in 1849 and Manjiro returned to the Whitfield farmhouse with a $350 share of the ship’s profit. Manjiro soon left again, this time sailing aboard a lumber ship bound for California. In the California gold fields the young man quickly made $600, then sailed for Hawaii. There he found three of his four Japanese fishing mates still alive. Manjiro and two of his friends, brothers Denzo and Goemon, decided to attempt to return home by finding work on a ship bound for Shanghai.

Manjiro finally reached his homeland in February 1851, ten years after he had been shipwrecked. He was imprisoned and interrogated for about thirty months by official who suspected he may have been converted to Christianity—which could be punished by death—or sent to Japan as a spy. Finally, he was allowed to return to his own village, where he was reunited with his mother.

As if the previous dozen years were not adventuresome enough, the next phase of his life was to be even more so. Because of Manjiro’s familiarity with western customs and technology and the English language, he was granted samurai status and began to tutor young men of the clan who ruled his village. Following Commodore Matthew Perry’s first visit to Japan in 1853, Manjiro was summoned to Japan’s capital to share his knowledge of the West with the government officials. He was elevated to a higher samurai rank and was allowed to take a family surname, something not allowed to commoners. He became Manjiro Nakahama and served to enlighten the Japanese in matters relating to America.

When Perry returned to Japan in 1854 to negotiate a treaty with Japan, Manjiro employed as an eavesdropper, hidden at the meeting place so he could pass on to his superiors the gist of the Americans’ conversations in English between themselves. It is thought that Manjiro’s diplomacy in portraying the Americans in the best possible light helped overcome some Japanese officials’ reservations about opening their ports to ships from the United States. The entire episode may have played out much differently without the subtle influence of the young man who had spent several years in Fairhaven.

Following the signing of the first treaty between the two nations, Manjiro returned twice to America, in 1860 and in 1870. During the second trip, Manjiro made a side trip to Fairhaven to see the Whitfields. Manjiro visited Captain and Mrs. Whitfield, schoolmate Job C. Tripp and other friends. Back in Japan he taught at the university in Tokyo. With his writings and tutoring, he spread English, modern methods of navigation and other western ideas throughout his homeland. On a lighter note, Manjiro is credited with introducing the necktie to Japan.

Manjiro Nakahama was 71 years old when he died in Tokyo in 1898. He had been married three times and had several children.

Twenty years after Manjiro’s death, his son, Dr. Toichiro Nakahama, through Japanese Ambassador Viscount Kikujiro Ishii, presented the Town of Fairhaven with a samurai sword in a ceremony at the high school stadium on July 4, 1918. Three quarters of a century later, on October 4, 1987, Fairhaven was honored with a visit by Japanese Crown Prince Akihito and Princess Michiko, now Emperor and Empress of Japan. In that year a sister-city agreement was signed between Fairhaven and Tosashimizu, Japan, formally linking two communities that had been bound by friendship for nearly 150 years.

Since Fairhaven and Tosashimizu have been sister cities, there have been many shared activities—visits by community dignitaries, little league baseball games, quilting exhibitions and student exchange programs.

In 2007, the uncertain fate of one of the homes on Cherry Street that had once been owned by the Capt. William Whitfield, prompted renowned Japanese physician Dr. Shigeaki Hinohara raised funds in Japan to purchase the house and renovate it. On May 7, 2009, Dr. Hinohara, along with 100 Japanese dignitaries, visited Fairhaven for the dedication of the Whitfield-Manjiro Friendship House* at 11 Cherry Street. The house was donated to the Town of Fairhaven. A few years later, at the age of 100, Dr. Hinohara returned to dedicate a number of flowering cherry trees he had donated, which were planted at Cooke Park just down the street from the house where Manjiro Nakahama stayed with the Whitfield family. Dr. Hinohara died in 2017 at the age of 105.

Every other October, in odd numbered years, Fairhaven has hosted a Manjiro Festival in the center of town, highlighting Japanese culture and celebrating the town’s tie with Manjiro’s homeland. More than 180 years after Manjiro Nakahama set foot in Fairhaven, his story is still celebrated with cultural exchange by young and old from Japan and Fairhaven.

*Maps of Oxford village published in 1850, 1851, and 1855, show that there was no house on the lot at 11 Cherry Street during the time Manjiro lived in Fairhaven. There is no record of a house at 11 Cherry Street until it appears on the 1855 map with William Whitfield as the owner. This is after Manjiro had returned to Japan. Capt. Whitfield died next door at his residence, 13 Cherry Street, in 1886, where he lived with his wife, his daughter Sybil, his son-in-law Joseph Omey, and his granddaughter Albertina “Allie” Omey. Allie Omey owned the Whitfield house at 13 Cherry Street until her death in 1959.

COPYRIGHT 2003, 2025 by Christopher J. Richard. All Rights Reserved. This is a slightly updated article first published in Fairhaven’s Monthly Navigator.

I found your site quite by accident. Had read your original version, and it was great to read again. Hope you are enjoying your retirement. We sure miss your contributions to the Fairhaven websites, and hope you and the family are doing well. Looking forward to more. Paul M

Great story.