Creating Cushman Park

At the turn of the 20th Century Fairhaven's benefactor turned a stagnant pond into a public park.

While the unique public buildings given to Fairhaven are the most noticeable gifts bestowed on the town by Standard Oil Company millionaire Henry H. Rogers, other undertakings were of a far grander scale but are not as obvious to the casual observer today. For example, the town’s public water system, installed in 1893, touches nearly every resident’s life daily. But Rogers’ final project involved the almost God-like act of moving a river and replacing a boggy pond with green park land.

At the turn of the 20th Century, there was a view of wetlands that was quite different from today’s. Human illness was often still attributed to odiferous “swamp gas” and modern pesticides were not available to help keep disease carrying mosquitos at bay. Eliminating fetid pools and marshes near populated areas was considered beneficial to the health and well-being of the population. Such ventures were regularly carried out by public health officials and volunteer village improvement societies. In fact, one of the stated purposes of our own Fairhaven Improvement Association, formed in 1883, was to “secure public health by better hygienic conditions in our homes and surroundings.”

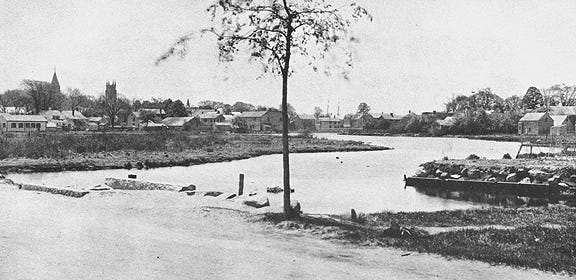

In Fairhaven’s case, the unhygienic acreage in question was the expanse between Bridge and Spring streets where the Herring River widened into the old Mill Pond.

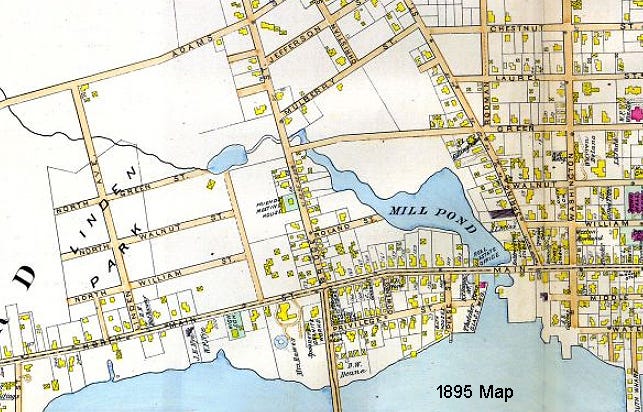

The Herring River began then, as it still does today, in the high northern part of town east of Alden Road. It crossed Long Road and Adams Street, curving southward as it approached what’s now Linden Avenue and Green Street. A small pond formed about where the high school stadium is today and the stream continued south across Bridge Street. Just a bit further south, extending from Green Street to Main Street was the big Mill Pond, once deep enough for whaleships to anchor in. The river exited the pond to the west, emptying into the Acushnet River.

The Herring River and Mill Pond separated Fairhaven Village on the south from Oxford to the north. Before a bridge was built across the stream in 1795 to extend Main Street northward, one traveled between the two villages by way of Adams Street.

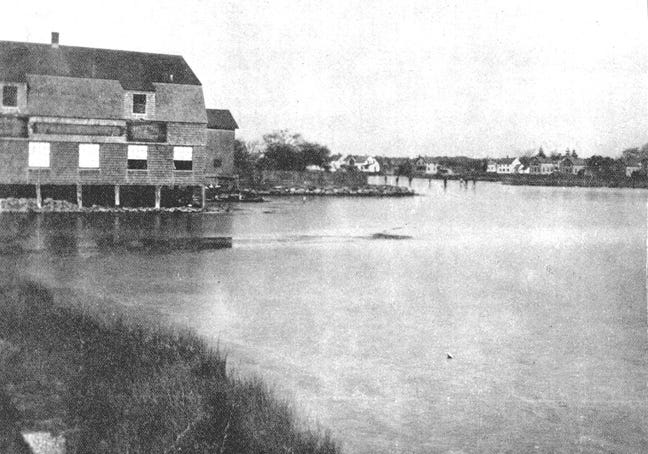

When the Main Street bridge was created, a mechanism was installed to harness the tides to power a mill built by Abner Vincent, hence the name Mill Pond. This had the effect over time of silting up the pond, making it shallower and its perimeter more fenny.

In 1894, Henry H. Rogers exerted considerable pressure on the county commissioners to get the Fairhaven entrance from the new Fairhaven-New Bedford Bridge moved about 300 feet north of Bridge Street, because it would allow a wide, straight road through unimproved property, which could be made more attractive. Whether or not at that early date he was already contemplating the new, wide Huttleston Avenue as the site of a high school is not known, but in July of 1902, Rogers bought 25 acres of the former John Hawes farm north of Bridge Street from the waterfront to Adams Street. This property fell on both sides of what’s now Route 6 and the sale included the Academy Building. By that time, the high school was certainly being planned.

But between the high school site and the cluster of Rogers buildings on Center Street lay acres of smelly swamp. It was time to call in the engineers.

The engineer Rogers favored was Joseph K. Nye, the flamboyant son of Nye Oil founder William F. Nye. In 1877, Nye had studied “practical mechanism” in a two-year program at MIT. He used his inventive skills at his father’s company, developing bottle-filling machines and other practical inventions. Joseph K. Nye had other interests besides oil refining, though. One was developing a public water supply. Nye left his father’s company and became the local agent for Standard Oil. About the same time, he set about trying to establish a water company in town and bought property near the Nasketucket River in east Fairhaven as a source for the water. Henry H. Rogers soon stepped in to finance the Fairhaven Water Company and Nye served as the private company’s president. (Revenue generated by the Fairhaven Water Company provided the operating funds for the Millicent Library.)

Nye became Rogers’ engineer for the daunting task of diverting the course of the Herring River and draining and filling the Mill Pond to create a public park. In November 1902 a newspaper story announced the project. In January 1903 a Town Meeting article was passed with the object “to abate a nuisance existing therein and for the preservation of the public health.” A crew of Italian laborers was hired to lay a concrete pipeline to channel the river underground. On Wednesday, April 15, the work began.

The huge concrete pipe, about six feet wide, was run through what was at the time vacant land. It was laid under Adams Street at Elm Avenue and followed the course of the river westward, turning south under Francis Street then southwest toward Green where the high school stadium is today. There, the conduit veered from the original river bed to run along the north side of Huttleston Avenue, under what was to become the front lawn of Fairhaven High School, across Main Street and to the Acushnet River just north of the bridge.

Once water no longer fed into the Mill Pond basin, earth could be transported in to fill it. This being the days before big dump trucks, a temporary, narrow gauge train track was laid along the north side of Bridge Street between the fill site and a “gravel hill” about a mile to the east, where Fairhaven’s landfill is now located. At the east end of the track, the fifteen-car train was filled by a modern steam shovel. An engine then pulled the train, led by a flag man to stop traffic at intersections, to the pond where the cars were emptied.

The area of the pond itself was about 5 1/2 acres, with about eight additional acres of swampiness around it. This surrounding area, primarily owned by dwellers on Bridge, Main, Spring and Green streets, had to be acquired. Joseph Nye handled “something like a hundred claims on account of land taken,” according to a 1905 newspaper account.

In a few cases houses were bought and moved. Where Park Avenue was going to be laid out to connect the park to Huttleston Avenue, two homes were moved. One went from the south side of Bridge Street to Holcomb Street and another, the “Blossom House,” from the north side of Bridge Street to the corner of Spring and Pleasant streets. The newspaper noted how quickly these houses were moved using the town’s steam-powered street roller to pull them as workers laid rollers and wooden planks along the ground in front. Another house was moved from Spring Street because the town planned to extend Walnut Street northward into the new park.

The filling of the pond was begun in the summer of 1903 on the Green Street side of the tract and progressed westward toward Main Street. At the Main Street end of the project, a thirty-inch drain pipe was installed so the water forced out of the pond would drain into the harbor instead of spreading onto the adjacent properties. Additional drains were run into the sewer system at Spring Street, which also emptied into the Acushnet River. Thousands upon thousands of cubic yards of earth were dumped into the pond, which was far deeper than had been estimated.

In early June 1905 a reporter noted “nearly all the water has disappeared.” By October, close to 200,000 tons* of fill had been consumed by the pond and swamp. The mud almost consumed a horse on one occasion and an Italian workman on another, but in both cases the sinking victims were hauled out in time.

The filling and grading of the Mill Pond and its surroundings created another problem. Raising the ground level in the park area forced the engineers to raise the grade of Bridge Street by two to three feet in places. This meant that 25 houses had to be lifted up and reset on higher foundations.

By 1905, another new element had been added to this massive earth moving project. In April a “groundbreaking” ceremony for the new high school was held, although the ground over there had been pretty well broken by the laying of the concrete conduit to divert the Herring River. But a great deal of additional filling had to be done, lest Rogers’ best loved project be nicknamed the “Castle in the Swamp.” The old Hawes ice pond was filled and the land on the north side of Huttleston Avenue was graded.

The layout of the new “Park Street,” now known as Park Avenue, was accepted in 1905. The plan indicated that the median strip in the two-lane avenue was precisely aligned with the “center line of Fairhaven High School.” In September 1906 the work in filling around the high school was finished and the tracks for the rail cars were finally taken up.

It would still be more than two years before the new park was turned over to the town. Landscaping of the area included the paving of footpaths and wider “avenues” which curved through the property. Many trees and ornamental shrubs were planted under the supervision of horticulturalist James Garthley. In a 1906 article in the New Bedford Standard, writer Arthur Brown Sherman noted, “a large oval of gravel remains in the centre, upon which it is proposed to erect a band stand.” If that particular band stand was ever installed, it didn’t last long and has been long forgotten. It is likely that it was one of the many small (and large) projects that got dropped when Henry H. Rogers died in May of 1909. (The band shell standing today on the east side of the park was given to the town in 1957, built by the members of the Fairhaven Junior Chamber of Commerce, who raised $7,000 for its construction. They were aided in their endeavor by the Fairhaven Improvement Association, which contributed $1,000 to the cause. It was dedicated to the memory of music teacher Anna B. Trowbridge.)

Once a lush green lawn was established and the ornamental plantings took root, the new park was turned over to the town at a Special Town Meeting held on October 28, 1908, at the Town Hall. Rogers asked that the park be named after Robert Cushman, an ancestor of his who had helped to organize the voyage of the Mayflower to the New World in 1620.

While the work was being done on Cushman Park, another piece of park land was being created between Main and Middle streets. This property, outfitted with fine tennis courts, was a gift of Warren Delano II. In the early 1960s the town, against the wishes of some members of the Delano family, sold this parcel for commercial use and it became a car lot.

Cushman Park has fared better, although today it bears little resemblance to what Rogers gave us. Ball fields, flood lights, tennis courts and the high school track have replaced the tree lined avenues. But modern times have brought improvements, too. Even Rogers’ engineers did not eliminate local flooding during heavy rains. More recent work to Cushman Park in the 1990s as part of the high school expansion project addressed some drainage problems within the park.

More than one hundred years after Rogers gave it to us, Cushman Park is still a popular and well used public space.

COPYRIGHT 2008 by Christopher J. Richard. All Rights Reserved. This story was originally published in Fairhaven’s Monthly Navigator.